Hello WFCAT fans, I’m going to commit a huge SEO faux-pas here and write this article about eulogies because I’m getting older, and it just seems like people I know are dying everywhere. Facebook is a disaster for me. It used to be my happy place, but now I find so many sad things happening to my peers with the loss of their loved ones that I feel compelled to try to help as a writer.

I write for children, edit for children, and publish for children, and I spend my days thinking about how to engage children in stories and books in meaningful ways. But I don’t spend a whole lotta time thinking about death when it comes to them, though that is a real legit thing that we as children’s book writers should write about, for sure. So maybe I will write on that one day. But for now bear with me as I change the channel and talk about this.

I am not an expert eulogy writer; that’s for sure. But who really gets formal training for this? Right? But I do know that when my father passed, I was suddenly nominated to write the eulogy WHILE grieving. IT SUCKS. Sorry, Dad, but when all you want to do is go into a hole and cry, the last thing you wanna do is write something compelling AND stand up and read it aloud to a room packed with people – half of whom you don’t even know. It’s far worse than the book signing where no one shows up or when the bookseller didn’t even remember you were coming!

And in true, CLIU-style, I will break down the eulogy for you in my usual analytical style so you can keep a few pointers in mind when you write yours for whomever it may be that you have lost. (BTW, I am very sorry for your loss if you got this far, and I know, too, that you may be very sick of people apologizing to you for your loss, but this is how it is.) I am happy that you found this article though, and I hope it will give you some sense of joy or relief, no matter how small, that can be had, during this sucky time.

At any rate, I’m going to share with you the actual eulogy that I gave.

I don’t claim the spelling or grammar is perfect. No one will care, really. Just remember, that your audience is glad it’s not them standing up there. So here goes:

A Eulogy Written for My Father’s Funeral (btw, you don’t need to title your eulogy. One less thing to think about!)

It seems like an impossible task to sum up my father in about 5 to 7 minutes. But fortunately for me, I realized that Dad unknowingly left me an outline. I know exactly what I’m going to do and where to start.

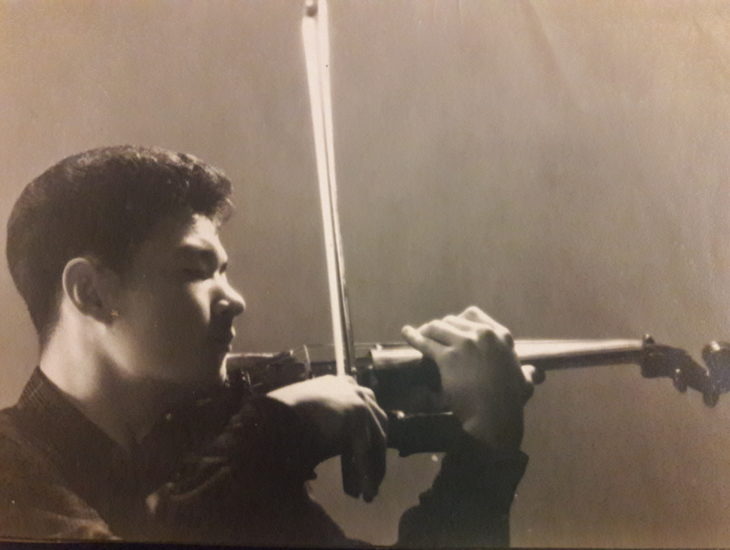

It begins with the violin.

If you can imagine our house with the three children, who all were taught to play, you would hear my father cracking watermelon seeds, as he watched TV, listening to us practice. His voice would boom, HIGHER, LOWER, HIGHER [make spitting sound] -and if we were still messing it up, he would take the instrument and show us. Little did I know the history of Dad and his violin until I read his memoir. His father would pay him to play the violin to keep Dad out of trouble. My father was so proud when he clocked five hours of practice in one day, that my grandfather paid up and promptly took to a movie. As you can imagine Dad got pretty good. To hear my father play was not only one of the reasons my mother fell in love with him, but one of the most amazing things you could ever hear coming out of a wooden instrument. I believe the violin in many ways symbolized to my father, Honor. My father honored my grandfather for many things, including giving him those lessons. It was this same fatherly love that gave Dad the violin and the violin to us.

There’s another word besides my father’s love of violin that defined my father—integrity. Daddy always had a strong sense of what was right versus wrong, especially when it came to our Chinese heritage. When the real estate market turned upside down, our financial situation was pretty bad. We children often helped maintained the homes my father built on the weekends. I’ve painted enough surfaces to cover Disney World and pulled weeds for a continental forest. Often our parents would reward us with pizza and a rental movie after a hard days’ work but one day we decided to go to this plain-looking restaurant called Razor Clam. When the doors opened, we saw the Maître D in tuxedo and realized this was no Pizza Hut. Imagine Us, this Chinese family in Tulsa in the 80s, with paint on our clothes and in our hair. Did Daddy say, whoops, wrong kind of joint? No. We stayed.

My dad and William borrowed jackets from the restaurant. I ate escargot for the first time. We would dine like any other high-class family, even if we didn’t come close to looking like one. I don’t think he wanted us to think we Chinese weren’t good enough, even though at the time, I’m sure we kids were thinking – where’s the buffalo wings? But now I understand the significance of that memory. In the late 60s, when Dad was in college in the US, Dad did the same thing for Mom when despite changes in the law, a school administrator still wouldn’t allow Mom to hold a job as a foreign student. He refused to leave the man’s office and caused a scene, scaring the living crap out of the man. All because Dad had something called integrity, and he made sure we knew what was right and wrong.

There’s another thing about my dad that you may all have noticed. He’s like a bulldog with most things when he set his sights on something. Trying to dissuade my father would be like trying to stop a tsunami with a thimble. From putting together meticulous model airplanes with my brother, building giant hotels with shopping centers, shopping in Mexico for the best tequila, picking up a staple gun within a week of open-heart surgery, and even yes, planning this funeral, Daddy persists until the very end. I have pages of Dad’s writing in the hours before his passing – scraggly lines – with labels where he tried to tell me to build a spreadsheet to help plan his funeral. From picking out the music, the kind of flowers, to the color of Daddy’s tie, that was all my father. You are completely surrounded by my dad’s persistence.

Generosity. My father embodied this word. As an example, Daddy could not stand the fact that children were dying just going to the bathroom in poor orphanages in China because they would fall in the pits. So he built them bathrooms. Even in his last hours, he prayed for the lives of those he loved, from all of our relatives to even his doctors and nurses. But he still had one last gift to give. He made sure not to leave until he told Mom to please enjoy her life without him, travel, see the children, have fun. I think knowing that he could not take our mother with him was his most difficult gift to give. He gave her to us, to those he leaves behind, and with that, he was finally able to go.

Kindness. I would like to qualify this one a little bit, Daddy was very kind, but if you mix that with his ideas of honor, persistence, integrity and so on, you might get why he could get so mad about certain things that would leave the whole family wondering where he was going when he got out of the car in the middle of the highway, mad. But no matter what you went through with Dad, you still knew he was kind and whatever it was, it was coming from a good place, but I’ll take that word further for Dad. We will revise that to love.

You see, the Liu Family has certain qualities which my father made sure we knew–we were LIUs. Dad taught us that family is family. That friends are family. That even a complete stranger could be treated as family as quickly as you can say the word family. And when Family needed help, you stepped up. Just like many have done for our father from our Grandpa John and Grandma Lulu to Auntie Amy, Uncle David, Auntie Helen and Auntie Ruth, and all the generations of offspring that come from the Liu line. Just like my father’s colleagues who’ve had his back at the church, his tenants, the neighbor across the way, and the good friend that he meets at one of this favorite restaurants.

So it makes perfect sense, we are all here now, our Liu family including our extended family of friends, and those with us in earthly spirit and above, that you are gathered to support us and celebrate our father. Dad would call you all Honorary Lius, whether or not you share the same last name as me.

Daddy would want it this way, and I know he is forever thankful and appreciative that you are here. So now I shall recite for you, the Liu Family Motto, which I did not really know existed in written words, until he created it for his memoir. That was the outline he left me without even knowing it: his memoir, where he actually wrote “The Liu Family Motto: Honor, Integrity, Persistence, Generosity, and Kindness.†I am now bestowing this motto upon you on his behalf.

My father hopes all of you Lius will uphold the Liu family motto as much as I do.

Thank you.

That was the eulogy I gave. Now here are my tips if you feel like you really need someone to tell you what to do.

- Identify a purpose for your eulogy. Let this purpose be your guide. What is the main takeaway you want to give to your audience? Generally, eulogies are about respect, remembrance, and positive things, uplifting things. What is the uplifting purpose (even if you feel sad as all-get-out ) that you want to give to your eulogy and to the people who are listening to it? Write that down. Your purpose can simply be to make people remember what was wonderful about your loved one. Your purpose may be to inspire people based on the story of the loved one who passed. What is the point (or purpose) of your eulogy? If you don’t know, ask someone what they hope will be the purpose of your eulogy. They can help give you ideas.

- Say something they haven’t heard before. Not everyone at a typical funeral knows each other or knows all the dimensions of the person who has passed. If you’re standing up there, you may not either. But chances are you know something that they don’t. To make sure people listen to what you have to say, provide specific and concrete details that is new to many of them that makes the eulogy yours to tell. Call upon special memories that you have. What memories do you have that will make your story rich about who the person was to you? Share a brief anecdote or two about these special unique memories.

- Acknowledge what your audience knows. Connect. To balance things out, I remember thinking that I should share a few themes about my dad, that most people know, too. In fictional character development, readers love to hear about the many dimensions of any character. My dad had so many dimensions (as most people do, that can’t be covered in one eulogy or one book), but think about what your audience probably already knows about your loved one. Include memories and details you have that is likely a shared experience about the person. For example, was she/he compassionate, boisterous, painfully shy and a great listener? Identify those adjectives that you remember about your loved one, and share a story or two that touches on those qualities so your audience will connect with the person you are speaking of.

- Be authentic AND kind. Tell your story from your POV. You can’t please everyone, but you’re up there for a reason (whether it was voluntary or not). Was my father a perfect person? No. But I felt like I couldn’t speak for anyone else really, except from my own POV. I had to guess some things about my father but I backed it up with DETAIL so people would understand why I felt the way I did. KIND DETAILS are your friend in eulogies, I thought, when I wrote one. They are your friend in fictional writing. It’s a psychological thing about us humans. When we learn kind details about a person, we tend to care more about them. So I provided positive details about how my father would eat watermelon seeds, I provided details about how he said and did things – these details are strong memories in my mind. What KIND DETAILS do you remember that backup your authentic, unique and shared memories of your loved one?

- Be practical. Don’t complicate. Remember that your time is and should be limited. When I was thinking about doing the eulogy, our pastor was very clear about how long to make it. Think two minutes, for every 250 words when read slowly, for one double-spaced typewritten page. You can see how long my eulogy was. Not THAT long. This will really help you focus on being practical and not over-complicating something you want to simplify. No one wants to hear a eulogy that lasts for hours. Short and sweet. Ba-boom. In and out. I remember constantly telling myself not to go too far with too many stories or be too general that no one really sees the point of the eulogy. I found my purpose, I used stories and details (both unique memories and shared) to backup my purpose, and I concluded with that purpose. I did not try to wander or meander far from that.

- Bonus tip: Bring it full circle. Seriously, if you only do some of these things, you’re going to be good. But if you’re the type that really wants to bring any piece of writing home, you do what I call, bring it full circle. You start with a hint of something and you bring back the detail at the end. For me it was the outline. I hinted that Dad gave me an outline and then later, I explained how I got that outline. Seems really lucky, right? That my father would give me an outline? Well it wasn’t; it took some thinking. And the main question I asked myself was … What would Dad want to say to all of us at his funeral? What would be his outline? What would be your loved ones’ outline? And maybe this is how you bring it full circle. Find the outline to guide your purpose. Work in the hint at the beginning. Then tie it up with the answer at the end. The outline for me was my dad’s memoir. This is the detail I bring in at the end, that explains how I knew to say what I did. This was really just my architected, analytical thinking and not a miracle. It took me a while to figure out how to bring it full circle. I initially started with memories and the violin and what my dad meant to me. The rest was done by the professional writer in me.

- Second Bonus Tip:Â I remember feeling like I was worried I would cry throughout the whole thing, and no one would understand me, so to prevent that from happening, I read my eulogy out loud and at a slow pace, several times before I had to speak. This way, I cried the first couple of times I read it, but by the third time, I was over the crying and the eulogy was just words on a page that needed to be read to people at a funeral. I did cry a little during the actual reading but not like I had when I read it aloud the first or second and third time. So I would suggest you read aloud your work to yourself or someone you feel comfortable with a few times or more, before you read it at the funeral.

- ABOVE ALL: If you’re feeling overwhelmed from all of this advice, DON’T WORRY (impossible, right?). But my last tip for you is: Go back to tip #4. Probably my most important tip of all. Followed by #5. You don’t even need to type anything if you don’t want to. And #7. So three things.  Three is a good number. The rest is stuff you can pretend you never read. You’re going to do great.

Finally, if you feel this article may be useful to someone, please feel free to share it. Again, I hope that sharing this with others will make it just a little bit easier for someone else. That’s why I do what I do with kids’ books. That’s my purpose–not as a eulogist, but as a writer. So maybe this article does have something to do with kids’ book writing?

All my best,

Cynthea Liu

nicely said, Cynthea, I would expect no less from you. I think the most important of your tips is to talk about the person/parent only you know. The one who helped to make you what you are today. This five/seven minutes was my gift to my parents when I wrote and gave eulogies for each them.

My sisters decided it would be me because, first, I am the ‘writer’ in the family. Second, I am the stand up speaker in the family. And third, as I told my parents multiple times, I always wanted to have the last word!

Be well, my friend.

Thanks, Teresa! Much love right back!